How to improvise (3/3)

How to improvise (3/3) – Some thoughts on Improvisation

Here we present an interesting Interview with Sonny Sharrock on Improvisation and Innovation.

Sonny Sharrock on Improvisation

Sonny Sharrock talking on different types of improvisers, the starting points for improvisation, and freedom as told to Dannette Hill

(Interview courtesy of jazzguitaronline.com)

My view of improvisation is very personal, full of love, anger, truth, lies, and, in the end (I hope), sense. According to Webster’s, to improvise is ‘to compose without previous preparation,’ or ‘to make or devise from what is at hand’.

There are three basic types of improvisers, the foremost being ‘the creator,’ who has an insatiable need to tell his story. For him, improvisation is only a tool. He plays each solo as if it were his last. He will not be compromised, nor will he be stopped.

Next is ‘the juggler,’ for whom the skill of improvisation is just as important as is the need to tell his story. The juggler gathers around him all of the things he has heard, and one by one tosses them into the air. With his skillful hands he cleverly keeps them aloft. He seldom drops an idea, because he knows them all so well.

Finally, there is ‘the tinkerer, whose improvisations are based on formulas and the instrument itself. His scientific manipulation of sound is laboratory-created and laboratory-bound forever. Making up a subcategory, if you will, is ‘the fool.’ He claims he is bored with music, so he has decided to make noise. Fool + Noise = Bullshit.

Throughout this discussion, I speak mainly about jazz music, for three reasons. First, because it is the music I know best, and it is also 90% improvised. Second, because classical music has not been improvised for at least 200 years. And last, because rock is pop music, with the singer and the song being the main components.

Rock instrumental solos fall mainly into the ‘juggler’ category. Regardless of the style of music, guitarists are such an insular group that they have become incestuous. They never listen to other instruments, but instead feed upon each other. It’s no wonder that everyone sounds the same. My main influences have always been horn players and drummers. I’m always slightly amused when I see a magazine mention Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, or John Coltrane along with an identification of their instrument. How can anyone think of being a musician and not be familiar with these men? If you ever hope to be a serious improviser, you have to know what, how, and why these and many others contributed to improvisation.

There are five main starting points for improvisation: melody, chords, scales/modes, tonal centers, and freedom. Most improvisers use a combination of these to obtain a particular sound. Throughout any improvisation, it helps to have a clear vision of the melody. I always strive to make my improvisations sound like a song. Melody is the first thing you learn and the last thing you hear before you impro- vise. Melody is the song. In my solo on ‘Broken Toys’ [Sonny Sharrock–Guitar, Enemy102) I improvise pieces of melody and use them to develop a new one, which becomes the song. Although a composer might use chords in conjunction with a melody, an improvisation based on the chords can be totally un-related to the original song. The technique for improvising on chord changes is fairly simple: You apply the appropriate scales and arpeggios to the chords. The hard part is to turn this into music. Charlie Parker and John Coltrane were probably the two greatest chordal improvisers who ever lived. They go beyond the standard technique, extending the scales and substituting and layering chords over the basic chord changes.

Although a composer might use chords in conjunction with a melody, an improvisation based on the chords can be totally un-related to the original song. The technique for improvising on chord changes is fairly simple: You apply the appropriate scales and arpeggios to the chords. The hard part is to turn this into music. Charlie Parker and John Coltrane were probably the two greatest chordal improvisers who ever lived. They go beyond the standard technique, extending the scales and substituting and layering chords over the basic chord changes.

Modal playing is the opposite of chordal improvisation. Instead of applying scales to chords, the scales create the harmony by emphasizing different notes. Soloing on tonal centers is different than modal and chordal playing, although it is a combination of the two. It simply uses either the most dominant tonality in a set of chord changes or a melody as the basis for a solo. Ornette Coleman is a master of this type of improvisation. He builds upon the melody, shifting his tonal center at will.

Finally, there is freedom–the most misunderstood and the most misused of all these elements. Freedom grows out of improvisation. It is both your emotional peak and your deeper self. It is the cry of jazz. The one rule for playing free is that you can play anything you want. A critic once remarked to me that it takes a great amount of taste to play free. He was wrong. Artists cannot be hampered by the restriction of taste. What playing free does take is imagination and confidence. In free playing, there is nothing else to stand on; it’s like walking in space. If you’re confident, you will not fall. The road forms beneath your feet as your imagination takes you places arrived at by no other means. My confidence in the beauty of the music carries me through. Coltrane’s Ascension [MCA, 29020] is the best example of freedom. Jugglers, tinkers, and fools try to play free; however, they will never succeed. It is reserved only for the masters.

I have referred to these techniques and devices as starting points, because they are what you should use to develop your improvisation. However, you must attempt to go beyond them.

Your solo should be a work of art, not a technical display, which is the most difficult part to trying to create great work. Your work must be great, or it is nothing. There is no middle ground.

A couple of years ago I toured Europe playing duos with saxophonists and other guitarists. We played in museums, coffee houses and any place where 20 to 30 people could fit into.

I took these gigs partly as a challenge, because I wanted to see if I could make music without a rhythm section behind me. About halfway through the first set on the first night, I realized that I had not gone to any of the beautiful places that music always takes me. Instead, I was struggling to come up with ideas and devices to make the music meaningful. I failed. Night after night I failed.

Duke Ellington was right, when he stated the first rule of music in his song title ‘it Don’t Mean A Thing If It Ain’t Got That Swing.’ I had forgotton this. I was trying to be interesting and clever, but instead I ended up playing bullshit.

Swing is based in confidence. It is the grace that you acquire after years of paying dues. Technically, it could be the emphasis placed on a note or part of a phrase that gives it movement; however, don’t forget that technique is only a beginning!

Swing is the dividing line between those who can play and those who can’t. Although the term was first used by jazz musicians, all music can swing in its own way; it simply depends on who’s playing it. Little Richard, Professor Longhair, Aaron Copland, Bo Diddley, Samuel Barber, and Sonny Terry all swing mightily without ever having played a note of jazz.

Music can be played at breakneck tempos, or as slow as the most painful blues. It can be composed or improvised, but swing it must. The swing that I use is the same swing that Benny Moten spoke of in the 1930s, that Bird and Dizzy used in the 50s, that Thelonious Monk turned inside out and Miles turned into a groove, and that Coltrane, Ornette, and Cecil Taylor set free. Goddammit, you really can’t play without it!

A rhythm section that plays static, highly arranged music behind a soloist doesn’t add much, but one that swings and improvises brings excitement and surprise to the music.

They make the music as wonderful as a first love and as devastating as death.

I love to play with drummers who play loud, long, and strong. Many years ago I had the good fortune of playing with Elvin Jones. I always pay a lot of attention to the way a drummer uses his ride i cymbal; Elvin plays it differently than anyone I’ve ever heard. His time is impeccable, but he doesn’t use the standard repetitive rhythm on the ride: Instead, he accents his ceaseless snare and tom patterns with it. Elvin’s high-hat cymbal does not always fall on the traditional second, and fourth beats; like his ride, it too is used to accent when necessary. With all of this coming at you at once, you hear and play differently. You swing or you die.

When I played with Elvin for the first time, I was afraid that I would be swallowed up by the music coming out of the drums. Eventually I got my nerve together and let myself go into the music. I started to develop melodies based on the rhythmic phrases. My confidence grew. I realized that I could not get lost, because I was in the hands of a master drummer and improviser. I had just met swing head-on for the first time.

All great improvisers spend many years developing their own sound. On the other hand, many guitarists buy their sound in little boxes, or, if they can afford it, in rack-mounted ‘stairways to heaven.’ If their individuality is ever questioned, they just point to their digital read-outs to show that their numbers are different from the other guy’s in town. Ultimately, your sound is your hands.

It may i take a lifetime for it to reach its fullness, but playing is a lifetime gig. if you’re not totally serious, do yourself and the world a favor and just do weddings, or buy a can of mousse and become a 6-string gladiator from hell and make some money.

Imitating someone else’s sound is unforgivable. I’ve known cats who began by trying to sound like their favorite players. Now 25 years later they are struggling to develop individuality–what a waste of time.

No one remembers the imitators. Miles is Miles, Coltrane is Coltrane, and Sonny Sharrock is Sonny Sharrock. For better or worse, you are your own truth.

Likewise, I hate to see soloists thinking onstage. At that point you should only be concerned with feeling. Trying to find places to insert your favorite licks is like painting by numbers: Always correct and always boring. When I’m improvising, I don’t want to spend time groping for notes, so I find all of the appropriate scales and modes within a few frets. By starting scales with your left-hand 3rd and 4th fingers, you can minimize your movement’ up and down the fretboard. This allows you to concentrate on creating melodies instead of performing gymnastics.

Remember that your improvisation must have feeling. It must swing and it must have beauty, be it the fragile beauty of a snowflake or the terrible beauty of an erupting volcano. Beauty–no matter how disturbing or how still–is always true. Don’t be afraid to let go of the things you know. Defy your weaker, safer self. Create. Make music.

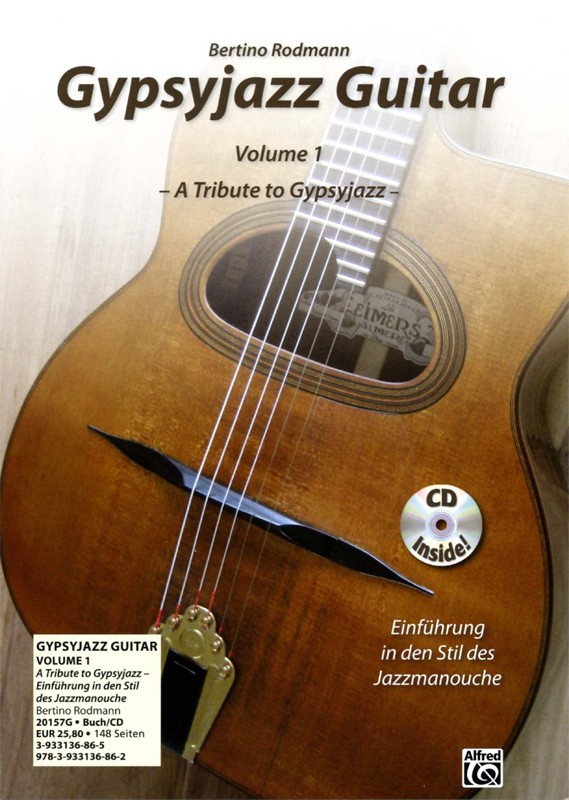

ADVERTISING

“Gypsyjazz Guitar – a tribute to Gypsyjazz“

“Gypsyjazz Guitar – a tribute to Gypsyjazz“

Gypsy-Jazz bzw. Jazz-Manouche ist der erste in Europa entstandene Jazzstil.

Seine Einflüsse kommen aus dem französischen Musette-Walzer, dem ungarischen Çsardas oder dem spanischen Flamenco, sowie der Sinti-Musik selbst, die von den Sinti-Musikern in Swing-Phrasierung interpretiert wurde.

Ziel des Buches: Nicht nur eine umfassende Gitarrenschule für Gypsy-Jazz Gitarre zu verfassen, die die rhythmischen und solistischen Aspekte der Gypsyjazz Gitarren-Spielweise vermittelt, sondern auch den Respekt gegenüber der uralten Tradition der Sinti.

Inhalt Teil 1: Rhythm Guitar: Comping, La Pompe-Rhythmus, Dead Notes, Gypsychords, Voicings, Blues-Kadenz, Chord Substitution

Inhalt Teil 2: Solo Guitar: Reststroke Picking, Arpeggio Picking, Sweptstroke Picking, Skalen, Arpeggien, Solo Licks

Verlag: Alfred Music Publishing GmbH; Auflage: 1 (15. Oktober 2011)

Sprachen: Deutsch / English ISBN-10: 3933136865 – ISBN-13: 978-3933136862

148 Seiten, mit Play-alongs und Noten & Tabulatur + Audio-CD Preis: 25,80

Erhältlich bei Amazon, Alfred Verlag oder www.bertino-guitarrist.com